What is it? A singleplayer adventure on a mysterious island populated with snack-based bugs.

Expect to pay $25

Developer: Young Horses

Publisher: Young Horses

Reviewed on: Windows 10, Intel Core i5-9600K, 16GB RAM, Nvidia RTX 2070 Super

Multiplayer? Nope

Out: November 11

Link: Epic Store

The bugsnax that affected me the most is the weenyworm. A weenyworm is a hot dog (with bun) that squiggles around in a circle saying “weenyworm” in a sing-songy voice that I’d describe as “nasal” if it didn’t imply a nose, which weenyworms don’t have. “Weeny… weenyworm,” it says again and again as it circles, embedding its voice in my head, waiting for me to capture it and feed it to a grumpus—a furry person, more or less, whose body parts turn into the bugsnax they eat.

What kind of grumpus would want a weenyworm for a leg or arm or nose? Almost all of them! Grumpuses love turning into bugsnax. It’s genuinely a bit disturbing how eager the characters of Bugsnax are to replace their body parts with sentient snack foods. Though they look it, grumpuses aren’t Justin Roiland-style shrieking monsters, either. They’re regular people, albeit bean-like and snaggletoothed. They’re cute, actually, and they even edge past wackiness and sentimentality and slice into human experience (when they’re not turning into weenyworms). I didn’t care for the actual bugsnax catching in Bugsnax, but working through the grumpus’s insecurities was pleasantly sweet—like a sweetiefly or a sprinklepede, perhaps.

Snack attack

As you may have guessed, the bugsnax are literally bug-like snacks: Grapeskeetos, pineantulas, sandopedes, and so on. Some of the wordplay is clever. The can-shaped Sodies come in regional variants: Mt Sodies on the peaks, Dr Sodies in the garden, and in the ocean they’re La Sodieux. Others are awkward contortions that don’t make much sense, like bannopers (banana grasshoppers that live in trees) and incherritos (inch worm burritos that live underground).

You play as a nameless journalist who was summoned to investigate these bugsnax by their discoverer, dashing adventurer Lizbert Megafig. Except when you arrive at Lizbert’s island she and her partner Eggabell are both missing, and the settlement they established is in ruins. The grumpuses who followed them there have scattered to the island’s conveniently distinct biomes to do their own things—all except hapless mayor Filbo, who enlists your help to reunite the town and find Lizbert and Eggabell.

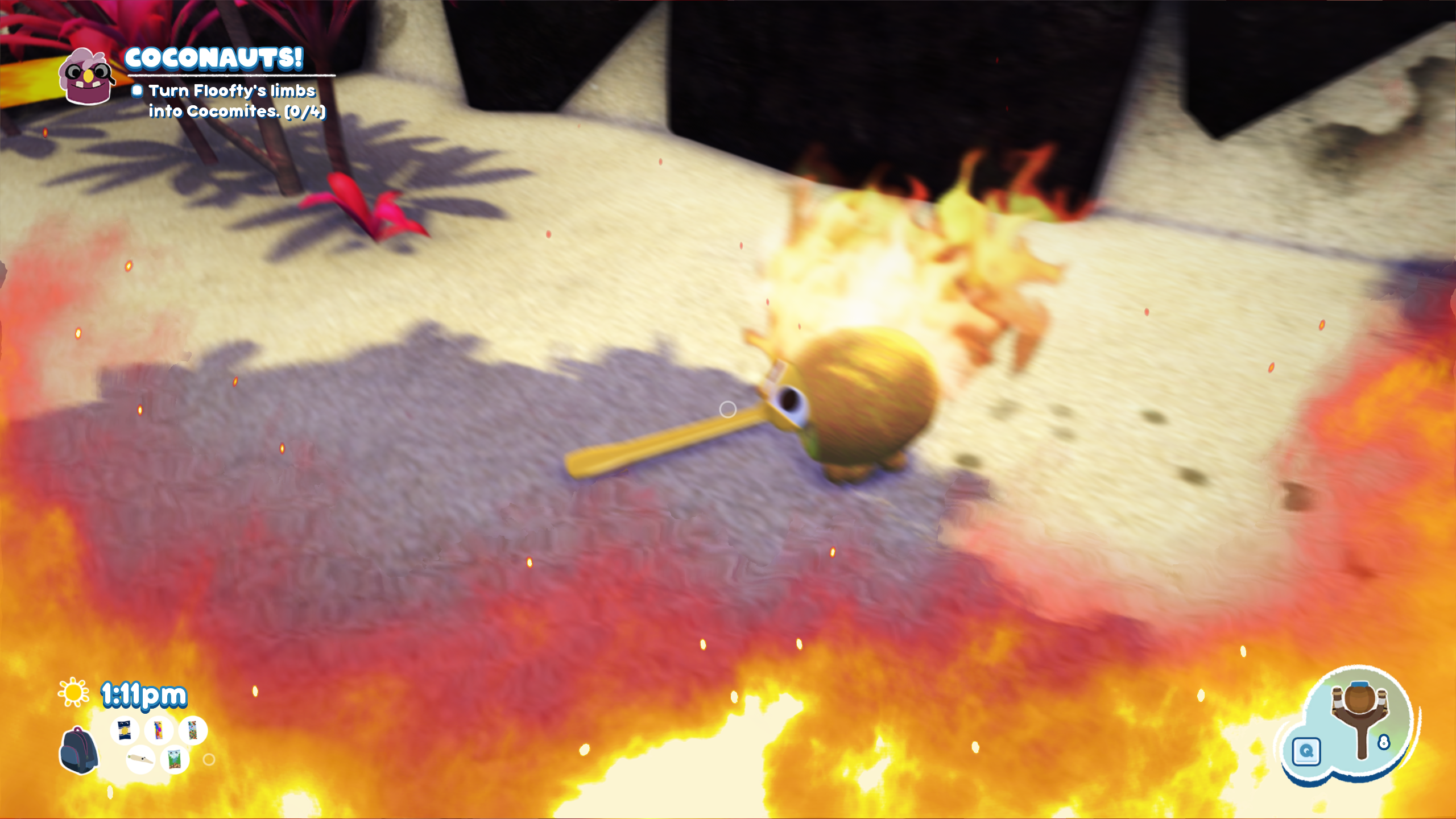

Over the course of ten-or-so hours, you’ll locate the scattered townsfolk in a forest glade, on the beach, among desert mesas, in an alpine forest, and on the peak of a volcanic mountain. Of course, none of them will come back to town straight away: You have to capture and feed them certain bugsnax to help them fulfill their objectives first.

At moments I really ached for the character, who mind you is an egg-shaped fur creature who is obsessed with eating bugs that are also snacks.

There are a variety of bugsnax-catching tools, but they all have very limited use cases, so Bugsnax is often just a matching game. Use the trap device on these kinds of bugsnax, but not these. Use the grappling hook on this one, but not that one. Shoot peanut butter on this bugnax to make it fall, and ketchup on that one to make its friend ram into it and knock it out. The closest I got to doing something creative was when I used a portable spring-loaded launcher to hurl a flaming bowl of noodles off the side of a cliff and then used the slingshot to splatter hot sauce all over the ground to lure the bowl into a pond, extinguishing its flames so that I could pick it up. It was more awkward than satisfying, like herding a cat with clown props.

Part of the joy of systems-driven games is testing their logical consistency, or discovering that the developer included a contingency plan for your most harebrained ideas, as in Spelunky 2, where an explosive mishap might lead to a shocking discovery, or at least comedy. There’s none of that in Bugsnax. If water and ice put out fire, shouldn’t ranch dressing? No, sauces can only attract or repel bugsnax. If I launch a bugsnax into a flying one, can I knock it out of the sky? No. What about the grappling hook? You can only use that in special cases. How do you crack an egg? Fire, for some reason. Everything must be done in the prescribed way.

There were also a few times I felt I might’ve been hindered by bugs (the software kind), but bugsnax hunting is such a sloppy business that it was hard to tell—certain things worked sometimes and not others, and I couldn’t say why.

Friends along the way

The consolation is that you don’t have to catch all that many bugsnax. Following the main quests, you only need to trap whatever bugsnax the grumpuses ask you to feed them, and that’s not nearly all of them. There were many I never attempted to snag, because I could tell how to do it just by looking at them, and I knew it would be fiddly and pointless. I did enjoy hearing all of their uncanny voices as I wandered around, though. The bugsnax all speak their own names like Pokémon, and some sound childlike, but others barely sound like they’re speaking a language at all. Their voices elevate a chemical in my blood that I can’t identify. Weeny… weenyworm.

The grumpus characters aren’t as mysterious, coming in obvious archetypes: The overdramatic pop star, the gossipy teen, the salesman, and so on. But they contain surprises. Snorpy, a standoffish scientist who thinks you might be part of the “grumpluminati,” is fond of giving hugs, and his buff boyfriend Chandlo has a genuine desire for self-actualization. Bugsnax is well-structured, too, with regular town parties that break up the questing and advance the plot.

I wish Bugsnax were more fun, but its cheerful grumpus body horror did change me, ever so slightly.

The leads, Lizbert and Eggabell, are missing, so their story plays out in video diaries. Fryda Wolff’s performance as Eggabell is the highlight—at moments I really ached for the character, who mind you is an egg-shaped fur creature who is obsessed with eating bugs that are also snacks. Wolff benefits from Eggabell being the best-observed character, a powder keg of self-doubt. (Side note: The story might get a bit too dark at the end for little kids, and the tragic result of failing a glitchy-feeling task near the end almost put me off of the whole thing, but it lets you retry the ending, so I’ve let it go.)

The environments aren’t as well-observed as the characters. They’re generic—as if they were based on forests and deserts from other videogames, rather than the places themselves—and manage to be both compact and sparse. There are parts of the desert area that are so barren, you’d think you clipped off the map and ended up in part of the background. The music and sound effects, on the other hand, had a soothing effect on me, especially the deep textured tone that marks the end of a quest—it feels like a brainwave realignment.

Bugsnax runs fine technically, and it’s better with a mouse and keyboard than a controller but accepts both. I wish it were more fun, but its cheerful grumpus body horror did change me, ever so slightly, and $25 is a fair price for its weird, sometimes grizzly story—though I suspect it’s better shared with someone who can laugh with you than played alone at a monitor, having your sense of self eroded by the repetition of the words “weeny, weenyworm.”